There were two major inventories of Charles I's art collection: one carried out by the king's keeper or surveyor (curator), Abraham van der Doort, from 1638 to 1640 and the 'Inventories and Valuations of the King's Goods' drawn up under the authority of the Commonwealth in the immediate aftermath of the king's execution on 30th January 1649.

The Van der Doort inventory

Abraham van der Doort's catalogue is a survey of the more important works in the collection and chiefly concerns the paintings and other notable objects (such as medals, sculpture, books, prints and drawings) on the 'King's Side' of Whitehall Palace, with briefer sections on Whitehall's 'Queen's Side', the Queen's House Greenwich, Greenwich Palace and Nonsuch Palace.

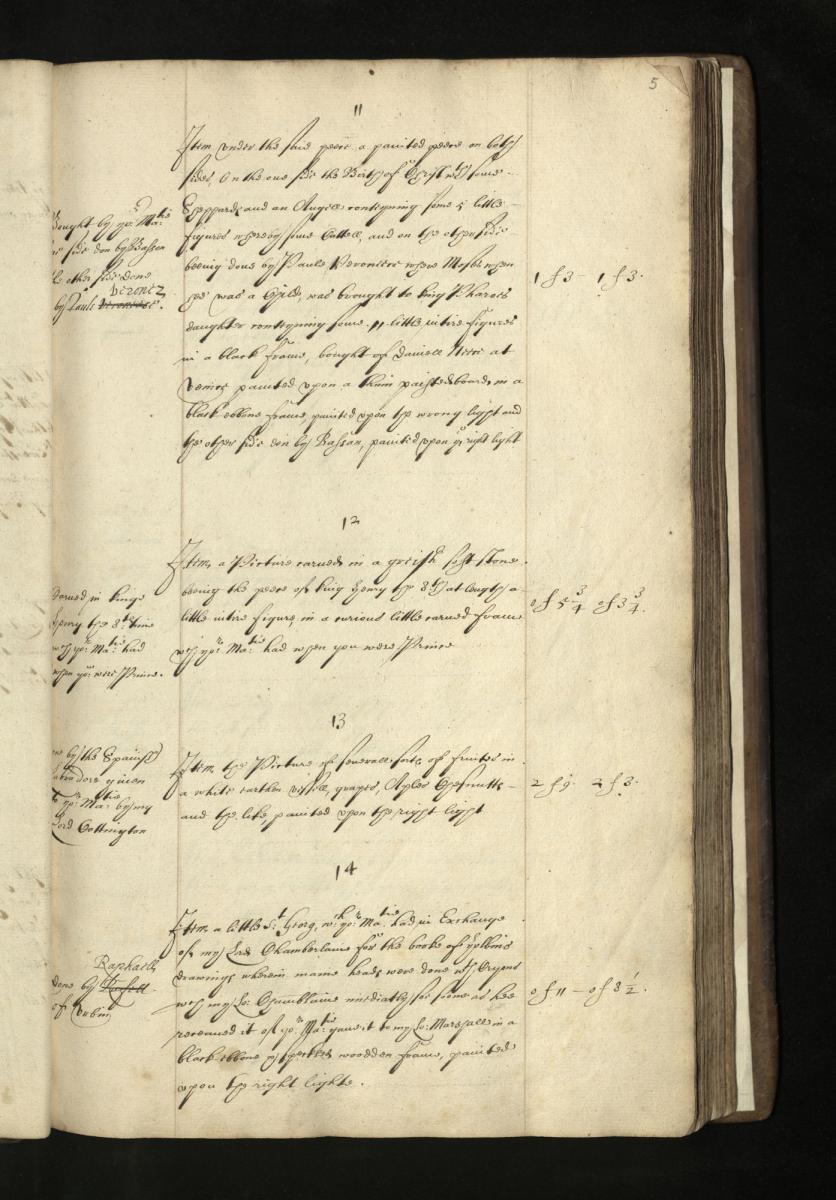

This is the chief record of Charles's collection due to the sheer depth of information it conveys, including detailed attributions, lengthy descriptions, (reasonably) precise measurements, and even provenance and hanging information. Van der Doort's working copy of the inventory, drafted mostly by an amanuensis, survives in the Bodleian Library at Oxford (MS. Ashmole 1514) complete with annotations and amendments in van der Doort's own hand. Some of his most common annotations are to say that an artwork is painted 'opan de raeht lijeht', with the illusion of light coming from the 'correct' direction, that is from the left as the viewer looks at it; or 'opan de wrang lijeht', meaning with the illusion of light coming from the 'wrong' direction, that is from the right as the viewer looks at it; or 'opan klaeht' signalling that an artwork is on 'cloth' meaning canvas. Such spellings and phraseology can seem incomprehensible to modern-day readers.

Charles's reason for requesting an inventory at this date remains unknown, but a precipitating factor could be that in 1637 he had acquired a group of 23 important Italian paintings from the dealer William Frizell. We can assume that Charles thought the hang of paintings at Whitehall Palace was representative enough of his plans for the Whitehall collection to commission a major stock-take at this stage (c.1638–40). Another factor might be that there were concerns about certain items going missing, as is evident in the inventory's finer detail.

Fair copies of individual rooms with particularly important and numerous contents, such as the Cabinet Room and King's Chair Room, inscribed with the date 1639, were produced by scribes and bound separately for the king's personal use. At least some of these fair copies (possibly all) are extant and can be found in Windsor's Royal Library (Cabinet Room, RCIN 1047433), Oxford's Bodleian Library (Cabinet Room, MS. Ashmole 1513) and the British Library (King's Chair Room, BL Add. MS. 10112).

As part of his warrant to care for the king's artworks, van der Doort was charged 'to order mark and number them, and to keep a register of them'. In addition to compiling the inventory, the keeper fixed descriptive notes to the back of paintings which detailed attribution, title, provenance and even date of acquisition.

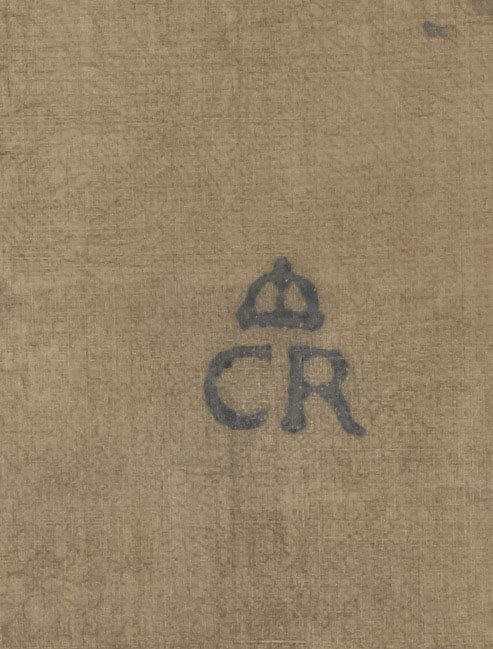

He is also thought to have been responsible for branding the monogram 'CR' (Charles I), 'CP' (Charles I when Prince of Wales) or 'HP' (Henry, Prince of Wales) on the reverse of panels and canvases (stenciling, in the case of canvases).

Explore the Van der Doort inventory

The V&A MS.

The Victoria and Albert Museum's MS. 86. J. 13 contains a list of the works found in the King's Gallery at St James's Palace, not included in any of van der Doort's manuscripts, and an alternative record of the contents of the Little Bi-Room between the Breakfast Chamber and Long Gallery (untitled), the Long Gallery, 'his Maties Closet by the Privy Gallerie in Whitehall' (otheriwse known as the Cabinet Room) and the Chair Room. This manuscript is not written by van der Doort or his assistant and might have been executed by another courtier, Sir James Palmer, and dated c.1640.

The Sale Inventory

The Sale Inventory was drawn up following the king's execution on the 30th January 1649 by a small team of representatives called trustees, appointed by the Commons with the purpose of recording and evaluating the king's possessions. The trustees included, among others, the Dutch painter Jan van Belcamp who had worked for the king under van der Doort.

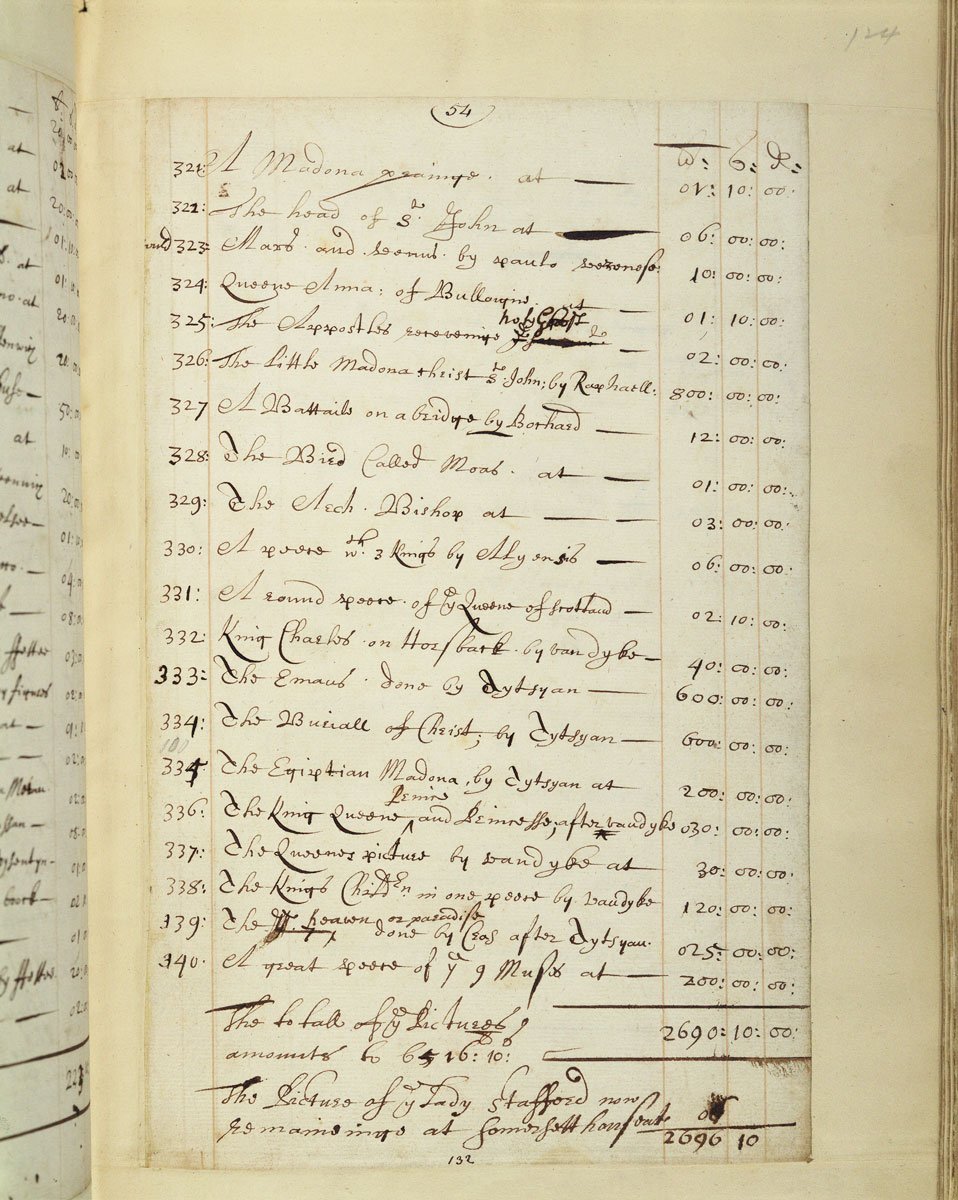

The Sale Inventory is the most complete record of the collection, spanning a range of royal residences and listing a considerable amount of decorative arts, jewelry and armour alongside paintings and sculpture. The inventory's breadth and comprehensiveness is remarkable, though its depth of information is demonstrably inferior to that contained in the earlier catalogue by van der Doort – even some of the most valuable paintings lack attributions – and it is thought that those working on the Sale did not have access to the Surveyor's work. The paintings alone were appraised for around £35,000.

The most important surviving document is in the National Archives (LR 2/124). It was assembled at the end of the eighteenth century by pasting the original folios from the 1649–51 document into a newly bound volume. Scholars have since detected four or five different secretary hands at work in the original text. Other important documents relating to the inventories are at the National Archives (SP 29/447), Corsham Court (Corsham MS), and the Society of Antiquaries (MS. 108).

Transcriptions

Despite the extensive scholarship on the history of Charles I's collection, there have been only three attempts to transcribe the inventories in a comprehensive and scholarly manner.

- George Vertue's transcription with Horace Walpole's introduction, printed by William Bathoe in 1757, was an attempt to transcribe the bulk of van der Doort's inventory with brief sections from the Sale Inventory. It contained errors and misspellings but there was an effort to modernise the language.

- Sir Oliver Millar's transcription of Abraham van der Doort's catalogue published in the Walpole Society Volume 37 (1958–60) is a detailed and accurate transcription of all the existing contemporary sources relating to van der Doort's inventory. Note that Millar's information comes from a spread of source manuscripts, each slightly different. Millar's publication repeats the seventeenth-century spelling verbatim which although useful can cause confusion. There is an appendix which includes a portion of the Victoria and Albert Museum's MS. 86. J. 13, which as mentioned above contains a list of the works found in the King's Gallery at St James's Palace c.1640 and an alternative record of other rooms at Whitehall (this manuscript is not written by van der Doort or his assistant but might have been executed by another courtier, Sir James Palmer). The publication's footnotes give information on the twentieth-century locations (1960) of around 350 artworks.

- Sir Oliver Millar's transcription of the Sale Inventories published in the Walpole Society Volume 43 (1970–72) is a detailed and accurate transcription of all the existing contemporary sources relating to the Sale Inventories. Note that Millar's information comes from a spread of source manuscripts, each slightly different. The footnotes do not cover twentieth-century locations of the artworks.

Current knowledge

Where possible, alongside the text from the two source inventories, we give the title, artist name, dimensions and reference number as given by the current owner of the work, as well as a link to the owner or institution's website. Where we have not been able to identify the work in a current collection, we retain the original inventory information.